Wild (exotic) animals kept as pets suffer

The problems we're tackling:

Animals suffer during capture and transport

The journey for a wild animal in the exotic pet trade is cruel – and often deadly. Either poached from the wild or bred in captivity on a farm, these animals suffer long before they reach our homes. Often, they’re shipped long distances, and taken to countries vastly different from their original homes. Many exotic pets suffer and die in transit before they even reach their final destination.

In our investigations, we found that up to 66% of African grey parrots who have been poached from the wild for the exotic pet trade will die in transit.

No wild animal can have its needs entirely met when kept as an exotic pet

We know people purchase exotic pets because they’re animal lovers. Animals bring joy to our lives, so it’s understandable that we’d want them to be part of our home. But many exotic pet owners are unaware of the suffering their animals endure.

Suffering is inherent in a life of captivity for a wild animal. Captivity limits their natural behaviour and places both their mental and physical well-being at risk. Inadequate captive environments can result in chronic stress and poor physical health. Wild animals are not pets; they belong in their natural habitat.

Taken from the wild

Many exotic pets start their lives free in the wild where they are captured to be sold into the pet trade. Research has shown that the exotic pet trade is a key threat to many species’ survival with large-scale poaching and theft from the wild devastating natural populations – adding to existing threats such habitat loss and the trade in wildlife for trophies, traditional medicine and entertainment. The methods used to snatch these animals from their natural habitats are cruel and inhumane; the numbers involved are shocking. As many as 21% of wild African grey parrots, a species already in danger of extinction, are captured for sale into the exotic pet trade each year. Over 55,000 Indian star tortoises at only one trading hub were recorded to have been collected from the wild in a single year. And an estimated 90% of traded reptile species and half of traded individuals are wild caught. Capturing animals from the wild for the exotic pet trade is happening on an industrial scale with devastating results.

Animals that manage to survive the pain and suffering caused by capturing methods face a perilous journey. Sold on to traders, they will be packed into small containers or crates, unable to breathe or move. Crammed into these small spaces, many will suffocate, starve, or succumb to diseases. Suitcases are stuffed full of tortoises. Dark, half metre crates are filled with so many parrots that they crush each other. Up to two thirds of African grey parrots will die during transportation. For other species, the true numbers of those who do not make it is often unknown, but even a 1% mortality rate can equate to millions of animals due to the size and scale of the exotic pet trade.

Captive breeding

Many animals caught from the wild end up in captive breeding facilities or farms. Others are bred in captivity themselves and then kept to produce offspring again and again. The breeding industry causes its own set of distinct problems for the animals trapped within them. It is by no means safe or cruelty-free.

As a starter, being born in captivity does not make an animal domesticated - although they may become tame to the touch of humans, they are still wild animals. Also, the selective breeding that takes place to produce certain fur markings and scale patterns as well as altering the natural size can have a negative impact on the animals’ physical and mental health. This is particularly common in snakes and other reptiles as buyers increasingly want genetically altered versions, known as morphs, that bear little resemblance to their wild. Snakes and other reptiles who have been selectively bred to produce the most unique colours can show signs of neurological disorders, that impacts the animals’ welfare.

For those animals that survive the inhumane breeding industry, a life as a pet can cause further trauma. Research has shown that up to 75% of pet snakes, lizards and tortoises die within the first year in the home. With natural age ranges up to 120 years, it is thought that these deaths mostly occur from illnesses related to their captivity. Also, exotic pets have been observed to display behaviours that researchers have likened to emotional trauma in humans. Parrots rip out their own feathers due to isolation and chronic stress – not dissimilar to self-harm in humans. Asian otters and sugar gliders have been observed to display repetitive destructive behaviours when kept in captivity, similar to people suffering from obsessive compulsive behaviours.

Sold online

The rise of social media has increased people’s accessibility and desire to own exotic pets Our research has shown that first time buyers of exotic pets are influenced by the ‘cute’ videos they see across social media; people who have watched such video when considering buying a wild animal as pet are more likely to complete the purchase.

Social media has also become a key marketplace for wild animal sales. A wide variety of exotic species are for sale at the click of a button in a largely unregulated marketplace. We have identified Facebook and Kijiji as key online channels facilitating the sale of exotic pets. While Facebook committed publicly to ban the trade of endangered species on their platform – our evidence shows this is not working in practice. Endangered species continue to be listed on, often private, groups dedicated to these animals, making the buying and selling of wild animals all too easy.

In a home, there is no way to replicate the space and freedom that wild animals need.

In our investigations, we found numerous concerns that speak to the broader welfare issues related to the keeping of wild animals as pets, below some specific examples related to reptiles:

- Basic needs not met: a high number of snakes, lizards, tortoises, and turtles die within one year of becoming a pet.

- Insufficient nutrition: in our investigations, we found that captive green iguanas, turtles and other reptiles often suffer from soft bone disease due to poor diet.

- Unhealthy contact: Snakes kept as pets in Canada have been linked to a salmonella outbreak, involving hospitalizations,

- Confined in tiny spaces: Snakes are often kept in undersized tanks in which they aren’t able to stretch their body in full.

- Cruel captive breeding: artificial breeding in captivity can cause ball pythons serious genetic defects

Risks to human health

Zoonotic diseases (diseases that can be transmitted from animals to humans) pose a significant risk to human health. They cause approximately a billion cases of human illness and millions of deaths every year. At a global level, according to one estimate, the economic damage caused by emerging zoonoses are hundreds of billions US dollars in the past 20 years and in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic have caused an estimated 5.2% contraction in the global GDP.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and most infectious disease experts agree that the origins of future human pandemics are likely to be zoonotic, with wildlife emerging as the primary source. 75% of new or emerging infectious diseases over the past decade originated from animals and principally from wildlife (e.g., SARS, MERS, Ebola, and COVID-19).

Wild animals kept as exotic pets can be a source of infectious disease and stressed animals, with compromised immune systems are more prone to contracting and shedding pathogens, increasing the likelihood of making people ill. Exposure to these pathogens can happen at pet expos, stores, or when bringing a wild animal into a home, the risk of you or your family contracting an infectious zoonotic disease is significant.

35% of zoonotic diseases in humans have been linked to an exotic pet.

Is that animal wild or domesticated?

You might be surprised!

Canadians love animals and many of us share our homes with a range of pets. But there is a stark difference between a dog or a cat as a pet and a parrot or a Ball python. So, what’s the difference between owning a dog and a parrot? A lot in fact. Here we define the different types of animals and explain why some are more suitable as pets than others.

Wild (exotic) animals vs domesticated animals

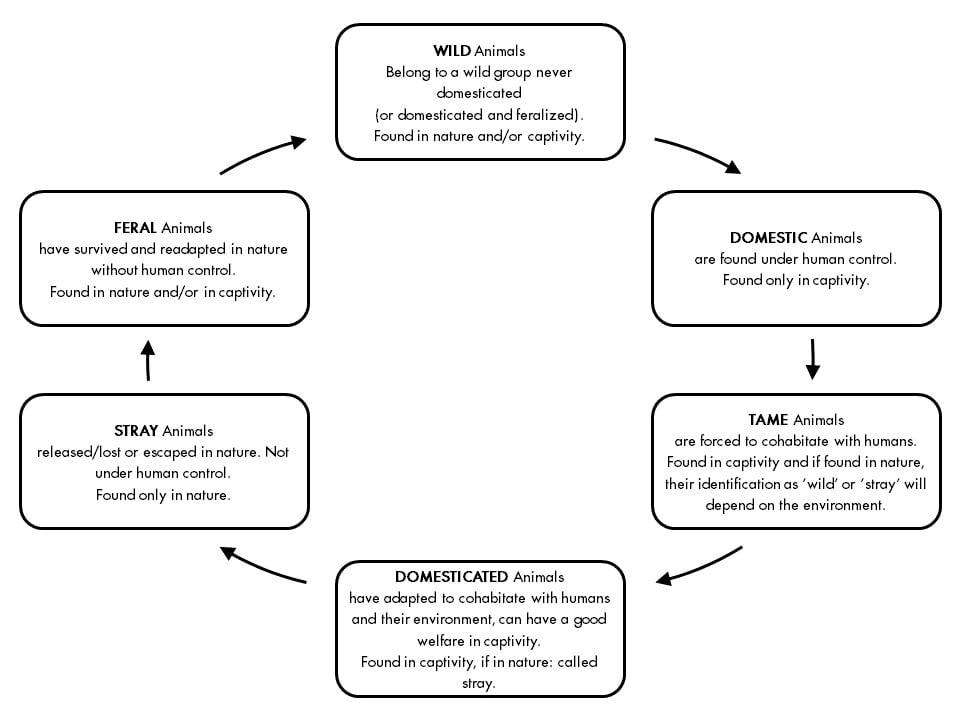

The terminology around the classification of animals is highly confusing. Terms like wild, domesticated and exotic are often used interchangeably and, adding to the confusion, our laws and regulations use a variety of inconsistent definitions to describe the origin of an animal. Classifying wild animals as domesticated can lead to great suffering because wild animals belong in the wild, not in our homes.

For guidance and clarification purposes, below are explanations of the different terms:

Domesticated animal – applies to a group of animals (a single animal cannot be domesticated) who have been selectively bred over thousands of years for specific traits, affecting biological, behavioural and genetic processes, that make the animals in the group better-suited for living alongside humans. Dogs, cats, horses and cattle are all examples of domesticated animals.

Domestic animal – animals who are kept in captivity by humans regardless if the animal is wild, tame, domesticated, etc.; is not an indication of the suitability of an animal to live in captivity. For example, a tiger kept as a pet is a domestic animal, however they are still very susceptible to tremendous suffering because tigers are not domesticated but wild animals.

Wild animal – belong to a group of animals who have never been domesticated. Wild animals live and breed in their natural environment without human interference. When bred in captivity, their behaviour might alter due to being in close proximity with humans, however they remain wild, having similar traits (behaviours and psychological needs) as their wild counterparts. For example, a captive bred Ball python is still a wild animal, they do not meet domestication criteria as described above and their behaviours and psychological needs are still identical to their ancestors/conspecifics.

Exotic animal – can be a wild or domesticated animal not native to a certain geographical region. For example, Grizzly bears are wild animals not native to Ontario and can therefore be considered as an exotic wild animal to the province. Llama’s on the other hand are a domesticated species exotic to Ontario and can therefore be classified as an exotic domesticated animal.

Tame animal – is a wild animal forced to live with humans, who may change their behaviour due to the close proximity with humans. For example, a healthy turkey vulture in the wild would not allow physical contact with a human, however once kept in captivity they can learn to tolerate physical contact.

Décory, M. S. M. (2019). A Universal Definition of" Domestication" to Unleash Global Animal Welfare Progress. In dA Derecho Animal: Forum of Animal Law Studies (Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 0039-55).

Evolution and domesticated animals

Pets like cats, dogs, and horses are domesticated animals, meaning they have been selectively bred over many generations for specific traits that make them better-suited to living alongside humans. The process of domestication occurs over thousands of years. It is believed that dogs may have been domesticated as early as 27,000-40,000 years ago and estimates of cat domestication are between 3,600 and 9,500 years ago.[1]

Domesticated animals, with the right care and conditions, are able to live with humans in captivity without suffering. In general, it is “easier” to take care of domesticated animals since they are able to live in similar conditions as to which humans live. For example, the room temperature we find comfortable is often also comfortable to a dog or a cat.

Exotic animals are most often wild animals

According to our research, Canada is home to 1.4 million exotic pets. Snakes, parrots, geckos, turtles, foxes, sugar gliders, scorpions and even tigers are just some of the wild exotic animals kept in Canadian homes.

Wild animals have not co-evolved with humans. Which means that these animals cannot thrive in a home-setting. Instead these animals require an environment that replicates their wild habitat which is almost impossible to do. The freedom and array of choices an animal has in the wild simply cannot be provided in a captive setting. For example, Ball pythons live in a wide range of habitats, during the day they hide in burrows but at night they will leave their shelter to go hunt or find a mate.[2] In a home environment, Ball pythons are restricted to enclosures, with only one type of habitat, they are often kept solitary and do not have a choice what to eat and when. In addition, like most snakes, they are often kept in undersized enclosures, restricting basic body movements like stretching their full body.

Our desire to own non-traditional ‘pets’ fuels an international and often illegal trade of wildlife.[3] Many animals sold into the pet trade start their lives free in the wild where they are captured in often cruel and inhumane ways. They will be usually packed into small containers or crates for transportation purposes, in some instances not even able to breathe or move. Investigations by us and other organizations have found that mortality rates in the exotic pet supply chain are horrifically high, for example up to 66% of African grey parrots who have been poached from the wild for the exotic pet trade will die in transit.[4]

Exotic wild animals bred in captivity are still wild animals

A wild animal that is bred in captivity doesn’t stop being wild and is not more suitable to live a life in captivity. We found that a majority of Canadians are against the exotic pet industry using wild caught animals for the trade, however the exotic animal breeding industry causes its own set of distinct problems for the animals trapped within them.

Captive bred wild exotic animals are bred in volume and in unnatural circumstances. Unhealthy breeding practices, like inbreeding, are used to create animals with preferential traits and colours (known as morphs), which can have severe welfare implications. This is particularly common in snakes and other reptiles as buyers increasingly want genetically altered versions of animals that bear little resemblance to their wild counterparts. In Canada, there is little regulatory oversight on breeding practices, allowing breeders to operate as they wish.

Tamed animals are still wild animals

Some wild animals born in captivity or captured in the wild may be more tolerant to humans, but this does not mean that they are domesticated. A wild animal may grow accustomed to people, but they remain wild animals with wild instincts, and suffer in captivity.

The easiest way to recognize a wild animal? Whenever an animal cannot naturally cohabit the space you live in but instead requires specialized housing (e.g., live in a terrarium), climate conditions (e.g., temperature and humidity) or behaviours (e.g., digging, swimming, etc.) there is a significantly high likelihood that this animal is wild.

Sources

[1] Bluecross and The Born Free Foundation, 2015, One Click Away: An investigation into the online sale of exotic animals as pets.

[2] Auliya, M. & Schmitz, A. 2010. Python regius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2010 and Toudonou, Christian AS. 2015. Ball python Python regius. CITES.

[3] Warwick et al, 2018, Exotic pet suitability: Understanding some problems and using a labelling system to aid animal welfare, environment and consumer protection, Journal of Veterinary Behavior.

[4] McGowan, P., 2001, CITES Review of Significant Trade 2006, Birdlife International 2015, CITES 2013 Available from: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/cop/17/prop/GAPsittacus_erithacus_EN.pdf [Accessed 24 Jan 2019]

Case study: Parrots – Wild at heart

African grey parrots are incredible animals. They are highly social and are known to fly several kilometers each day to forage for food. They are among the most popular bird species kept in Europe, the USA and the Middle East.

A life alone in a cage is a stark contrast to life in the wild.

Wild African grey parrots live in Western and Central Africa. African grey parrots, like any other parrot you see for sale online or in the pet shop are wild animals. While they may have been born in captivity, their parents or grandparents have been caught from the wild. Offspring of wild animals are still wild animals and retain their natural instincts and needs.

Despite the wild nature of parrots, over half of Canadians believe this family of birds are acceptable pets.[5] They would be forgiven for thinking this because the pet industry provides little information about their unique needs, complex behaviours and the high level of care required to look after these animals.

With a lifespan of over 60 years, parrots can easily outlive their owners. Because of their long lifespan and wild nature, it is common for parrots to be rehomed repeatedly during their lifetime. Their highly socialized nature means that when they are alone in a cage, they will suffer from isolation and boredom often resorting to plucking their feathers out of their body (also known as self-mutilating behaviours) and constant screaming. This difficult behaviour leads many owners to surrender their parrot. With many bird sanctuaries already at capacity, countless parrots are at risk of a life of suffering in captivity.

Dr. Alix Wilson, an exotic pet veterinarian, cares for exotic animals, and told us about her experience treating parrots:

"I see badly cared for birds every single day. But every day I see birds whose owners love them dearly but aren’t taking proper care of them. They simply don’t know what they are taking on. And every day we are called by people who are wanting to rehome their birds."

African grey parrots are among the most popular bird species kept in Europe, the USA and the Middle East. With many bird sanctuaries already at capacity, countless parrots are at risk of a life of suffering in captivity.

Sources

[5] World Animal Protection Brand Tracking, 2018.

What you can do

While keeping some exotic pets may involve less suffering than others, wild animals cannot have their needs met entirely in captivity. Only domesticated animals, like cats and dogs, should be kept in home environments because their needs can be met.

If you already own an exotic animal and haven’t done already, please seek expert advice from a specialized veterinarian to ensure you’re meeting as many of their welfare needs as possible. We encourage you to continue to give your exotic animal the best life possible, for as long as you can.

Never release an exotic pet into the wild. Most animals cannot survive and will either die from starvation, the weather or will be killed by other predators. While most released animals will likely die, some may survive and establish themselves in a non-native environment and become an invasive species. When this occurs, it can have serious negative implications for the local, native species of animals and their ecosystems. Examples of invasive species in Canada include red-eared sliders, Italian wall lizards and American bullfrogs.

To help keep wild animals in the wild where they belong, we ask you to commit to not purchasing another exotic pet in the future and to refrain from breeding the one you own.

Consider adopting a domesticated pet instead of buying an exotic animal as a pet

Don’t buy exotic pets. We encourage everyone to appreciate and respect wild animals where they belong – in the wild.

We should only share our homes with domesticated animals who have evolved over thousands of years to be our companions and whose needs, when taking care of properly, can be completely met as pets.

Join our pledge to commit to keeping wild animals in the wild

Take action against the wildlife pet trade today by signing the pledge to never buy an exotic wild animal. Help us protect wildlife by keeping them where they belong. In the wild.